American Civil War

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The American Civil War (1861–1865), amongst other names also known as the War Between the States, was a civil war in the United States of America. Eleven Southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America, also known as "the Confederacy". Led by Jefferson Davis, they fought against the United States (the Union), which was supported by all the free states (where slavery had been abolished) and by five slave states that became known as the border states.

In the presidential election of 1860, the Republican Party, led by Abraham Lincoln, had campaigned against the expansion of slavery beyond the states in which it already existed. In response to the Republican victory in that election, seven states declared their secession from the Union before Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861. Both the outgoing administration of President James Buchanan and Lincoln's incoming administration rejected the legality of secession, considering it rebellion. Several other slave states rejected calls for secession at this point.

Hostilities began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces attacked a US military installation at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. Lincoln responded by calling for a volunteer army from each state to recapture federal property. This led to declarations of secession by four more slave states. Both sides raised armies as the Union assumed control of the border states early in the war and established a naval blockade. In September 1862, Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation made ending slavery in the South a war goal,[1] and dissuaded the British from intervening.[2]

Confederate commander Robert E. Lee won battles in the east, but in 1863 his northward advance was turned back with heavy casualties after the Battle of Gettysburg. To the west, the Union gained control of the Mississippi River after their capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi, thereby splitting the Confederacy in two. The Union was able to capitalize on its long-term advantages in men and material by 1864 when Ulysses S. Grant fought battles of attrition against Lee, while Union general William Tecumseh Sherman captured Atlanta, Georgia, and marched to the sea. Confederate resistance collapsed after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

The American Civil War was one of the earliest true industrial wars in human history. Railroads, steamships, mass-produced weapons, and various other military devices were employed extensively. The practices of total war, developed by Sherman in Georgia, and of trench warfare around Petersburg foreshadowed World War I in Europe. It remains the deadliest war in American history, resulting in the deaths of 620,000 soldiers and an undetermined number of civilian casualties. Ten percent of all Northern males 20–45 years of age died, as did 30 percent of all Southern white males aged 18–40.[3] Victory for the North meant the end of the Confederacy and of slavery in the United States, and strengthened the role of the federal government. The social, political, economic and racial issues of the war decisively shaped the reconstruction era that lasted to 1877.

Contents |

Causes of secession

| History of the United States | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series |

|

| Timeline | |

| Pre-Colonial period | |

| Colonial period | |

| 1776–1789 | |

| 1789–1849 | |

| 1849–1865 | |

| 1865–1918 | |

| 1918–1945 | |

| 1945–1964 | |

| 1964–1980 | |

| 1980–1991 | |

| 1991–present | |

| Topic | |

| Westward expansion | |

| Overseas expansion | |

| Diplomatic history | |

| Military history | |

| Technological and industrial history | |

| Economic history | |

| Cultural history | |

| Civil War | |

| History of the South | |

| Civil Rights (1896–1954) | |

| Civil Rights (1955–1968) | |

| Women's history | |

|

United States Portal |

The Abolitionist movement in the United States had roots in the Declaration of Independence. Slavery was banned in the Northwest Territory with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. By 1804 all the Northern states had passed laws to abolish slavery. Congress banned the African slave-trade in 1808, although slavery grew in new states in the deep south. The Union was divided along the Mason Dixon Line into the North (free of slaves), and the South, where slavery remained legal.[4]

Despite compromises in 1820 and 1850, the slavery issues exploded in the 1850s. Lincoln did not propose federal laws against slavery where it already existed, but he had, in his 1858 House Divided Speech, expressed a desire to "arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction."[5] Much of the political battle in the 1850s focused on the expansion of slavery into the newly created territories.[6][7] Both North and South assumed that if slavery could not expand it would wither and die.[8][9][10]

Southern fears of losing control of the federal government to antislavery forces, and Northern resentment of the influence that the Slave Power already wielded in government, brought the crisis to a head in the late 1850s. Sectional disagreements over the morality of slavery, the scope of democracy and the economic merits of free labor versus slave plantations caused the Whig and "Know-Nothing" parties to collapse, and new ones to arise (the Free Soil Party in 1848, the Republicans in 1854, the Constitutional Union in 1860). In 1860, the last remaining national political party, the Democratic Party, split along sectional lines.

Northerners ranging from the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison to the moderate Republican leader Lincoln[11] emphasized Jefferson's declaration that all men are created equal. Lincoln mentioned this proposition many times, including his 1863 Gettysburg Address.

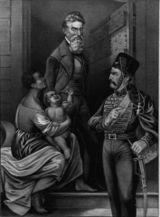

Almost all the inter-regional crises involved slavery, starting with debates on the three-fifths clause and a twenty-year extension of the African slave trade in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The 1793 invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney increased by fiftyfold the quantity of cotton that could be processed in a day and greatly increased the demand for slave labor in the South.[12] There was controversy over adding the slave state of Missouri to the Union that led to the Missouri Compromise of 1820. A gag rule prevented discussion in Congress of petitions for ending slavery from 1835–1844, while Manifest Destiny became an argument for gaining new territories, where slavery could expand. The acquisition of Texas as a slave state in 1845 along with territories won as a result of the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) resulted in the Compromise of 1850.[13] The Wilmot Proviso was an attempt by Northern politicians to exclude slavery from the territories conquered from Mexico. The extremely popular antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe greatly increased Northern opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.[14][15]

The 1854 Ostend Manifesto was an unsuccessful Southern attempt to annex Cuba as a slave state. The Second Party System broke down after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which replaced the Missouri Compromise ban on slavery with popular sovereignty, allowing the people of a territory to vote for or against slavery. The Bleeding Kansas controversy over the status of slavery in the Kansas Territory included massive vote fraud perpetrated by Missouri pro-slavery Border Ruffians. Vote fraud led pro-South Presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan to attempt to admit Kansas as a slave state. Buchanan supported the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution.[16]

Violence over the status of slavery in Kansas erupted with the Wakarusa War,[17] the Sacking of Lawrence,[18] the caning of Republican Charles Sumner by the Southerner Preston Brooks,[19][20] the Pottawatomie Massacre,[21] the Battle of Black Jack, the Battle of Osawatomie and the Marais des Cygnes massacre. The 1857 Supreme Court Dred Scott decision allowed slavery in the territories even where the majority opposed slavery, including Kansas.

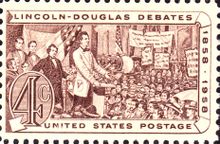

The Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 included Northern Democratic leader Stephen A. Douglas' Freeport Doctrine. This doctrine was an argument for thwarting the Dred Scott decision that, along with Douglas' defeat of the Lecompton Constitution, divided the Democratic Party between North and South. Northern abolitionist John Brown's raid at Harpers Ferry Armory was an attempt to incite slave insurrections in 1859.[22] The North-South split in the Democratic Party in 1860 due to the Southern demand for a slave code for the territories completed polarization of the nation between North and South.

Slavery

Support for secession was strongly correlated to the number of plantations in the region. States of the Deep South, which had the greatest concentration of plantations, were the first to secede. The upper South slave states of Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee had fewer plantations and rejected secession until the Fort Sumter crisis forced them to choose sides. Border states had fewer plantations still and never seceded.[23][24]

As of 1860 the percentage of Southern families that owned slaves has been estimated to be 43 percent in the lower South, 36 percent in the upper South and 22 percent in the border states that fought mostly for the Union.[25] Half the owners had one to four slaves. A total of 8000 planters owned 50 or more slaves in 1850 and only 1800 planters owned 100 or more; of the latter, 85% lived in the lower South, as opposed to one percent in the border states.[26]

Ninety-five percent of African-Americans lived in the South, comprising one third of the population there as opposed to one percent of the population of the North, chiefly in larger cities like New York and Philadelphia. Consequently, fears of eventual emancipation were much greater in the South than in the North.[27]

The Supreme Court decision of 1857 in Dred Scott v. Sandford escalated the controversy. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's decision said that slaves were "so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect".[28] Taney then overturned the Missouri Compromise, which banned slavery in territory north of the 36°30' parallel. He stated, "[T]he Act of Congress which prohibited a citizen from holding and owning [enslaved persons] in the territory of the United States north of the line therein is not warranted by the Constitution and is therefore void."[29] Democrats praised the Dred Scott decision, but Republicans branded it a "willful perversion" of the Constitution. They argued that if Scott could not legally file suit, the Supreme Court had no right to consider the Missouri Compromise's constitutionality. Lincoln warned that "the next Dred Scott decision"[30] could threaten Northern states with slavery.

Lincoln said, "This question of Slavery was more important than any other; indeed, so much more important has it become that no other national question can even get a hearing just at present."[31] The slavery issue was related to sectional competition for control of the territories,[32] and the Southern demand for a slave code for the territories was the issue used by Southern politicians to split the Democratic Party in two, which all but guaranteed the election of Lincoln and secession. When secession was an issue, South Carolina planter and state Senator John Townsend said that, "our enemies are about to take possession of the Government, that they intend to rule us according to the caprices of their fanatical theories, and according to the declared purposes of abolishing slavery."[33] Similar opinions were expressed throughout the South in editorials, political speeches and declarations of reasons for secession. Even though Lincoln had no plans to outlaw slavery where it existed, whites throughout the South expressed fears for the future of slavery.

Southern concerns included not only economic loss but also fears of racial equality.[34][35][36][37] The Texas Declaration of Causes for Secession[38][39] said that the non-slave-holding states were "proclaiming the debasing doctrine of equality of all men, irrespective of race or color", and that the African race "were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race". Alabama secessionist E. S. Dargan warned that whites and free blacks could not live together; if slaves were emancipated and remained in the South, "we ourselves would become the executioners of our own slaves. To this extent would the policy of our Northern enemies drive us; and thus would we not only be reduced to poverty, but what is still worse, we should be driven to crime, to the commission of sin."[40]

Beginning in the 1830s, the US Postmaster General refused to allow mail which carried abolition pamphlets to the South.[41] Northern teachers suspected of any tinge of abolitionism were expelled from the South, and abolitionist literature was banned. Southerners rejected the denials of Republicans that they were abolitionists.[42] The North felt threatened as well, for as Eric Foner concludes, "Northerners came to view slavery as the very antithesis of the good society, as well as a threat to their own fundamental values and interests."[43]

During the 1850s, slaves left the border states through sale, manumission and escape, and border states also had more free African-Americans and European immigrants than the lower South, which increased Southern fears that slavery was threatened with rapid extinction in this area. Such fears greatly increased Southern efforts to make Kansas a slave state. By 1860, the number of white border state families owning slaves plunged to only 16 percent of the total. Slaves sold to lower South states were owned by a smaller number of wealthy slave owners as the price of slaves increased.[44]

Even though Lincoln agreed to the Corwin Amendment, which would have protected slavery in existing states, secessionists claimed that such guarantees were meaningless. Besides the loss of Kansas to free soil Northerners, secessionists feared that the loss of slaves in the border states would lead to emancipation, and that upper South slave states might be the next dominoes to fall. They feared that Republicans would use patronage to incite slaves and antislavery Southern whites such as Hinton Rowan Helper. Then slavery in the lower South, like a "scorpion encircled by fire, would sting itself to death."[45]

Sectionalism

Sectionalism refers to the different economies, social structure, customs and political values of the North and South.[46][47] It increased steadily between 1800 and 1860 as the North, which phased slavery out of existence, industrialized, urbanized and built prosperous farms, while the deep South concentrated on plantation agriculture based on slave labor, together with subsistence farming for the poor whites. The South expanded into rich new lands in the Southwest (from Alabama to Texas).[48] However, slavery declined in the border states and could barely survive in cities and industrial areas (it was fading out in cities such as Baltimore, Louisville and St. Louis), so a South based on slavery was rural and non-industrial. On the other hand, as the demand for cotton grew the price of slaves soared. Historians have debated whether economic differences between the industrial Northeast and the agricultural South helped cause the war. Most historians now disagree with the economic determinism of historian Charles Beard in the 1920s and emphasize that Northern and Southern economies were largely complementary.[49]

Fears of slave revolts and abolitionist propaganda made the South militantly hostile to abolitionism.[50][51] Southerners complained that it was the North that was changing, and was prone to new "isms", while the South remained true to historic republican values of the Founding Fathers (many of whom owned slaves, including Washington, Jefferson and Madison). Lincoln said that Republicans were following the tradition of the framers of the Constitution (including the Northwest Ordinance and the Missouri Compromise) by preventing expansion of slavery.[52] The issue of accepting slavery (in the guise of rejecting slave-owning bishops and missionaries) split the largest religious denominations (the Methodist, Baptist and Presbyterian churches) into separate Northern and Southern denominations.[53] Industrialization meant that seven European immigrants out of eight settled in the North. The movement of twice as many whites leaving the South for the North as vice versa contributed to the South's defensive-aggressive political behavior.[54]

Nationalism and honor

Nationalism was a powerful force in the early 19th century, with famous spokesmen like Andrew Jackson and Daniel Webster. While practically all Northerners supported the Union, Southerners were split between those loyal to the entire United States (called "unionists") and those loyal primarily to the southern region and then the Confederacy.[55] C. Vann Woodward said of the latter group, "A great slave society...had grown up and miraculously flourished in the heart of a thoroughly bourgeois and partly puritanical republic. It had renounced its bourgeois origins and elaborated and painfully rationalized its institutional, legal, metaphysical, and religious defenses....When the crisis came it chose to fight. It proved to be the death struggle of a society, which went down in ruins."[56]

Insults to national honor greatly troubled people: Southerners thought the abolitionists who identified slave ownership as evil and sinful—as in Uncle Tom's Cabin (1854)—were deliberately besmirching their honor.[57] Of critical importance was the attempted slave insurrection led by abolitionist John Brown in 1859, which many in the South saw as the beginning of Northern efforts to start a race war that would kill vast numbers.[58]

States' rights

Everyone agreed that states had certain rights—but did those rights carry over when a citizen left that state? The Southern position was that citizens of every state had the right to take their property anywhere in the U.S. and not have it taken away—specifically they could bring their slaves anywhere and they would remain slaves. Northerners rejected this "right" because it would violate the right of a free state to outlaw slavery within its borders. Republicans committed to ending the expansion of slavery were among those opposed to any such right to bring slaves and slavery into the free states and territories. The Dred Scott Supreme Court decision of 1857 bolstered the Southern case within territories, and angered the North.[59]

Secondly the South argued that each state had the right to secede—leave the Union—at any time, that the Constitution was a "compact" or agreement among the states. Northerners (including President Buchanan) rejected that notion as opposed to the will of the Founding Fathers who said they were setting up a "perpetual union".[59] Historian James McPherson writes concerning states' rights and other non-slavery explanations:

While one or more of these interpretations remain popular among the Sons of Confederate Veterans and other Southern heritage groups, few professional historians now subscribe to them. Of all these interpretations, the state's-rights argument is perhaps the weakest. It fails to ask the question, state's rights for what purpose? State's rights, or sovereignty, was always more a means than an end, an instrument to achieve a certain goal more than a principle.[60]

Slave power

Antislavery forces in the North identified the "Slave Power" as a direct threat to republican values. They argued that rich slave owners were using political power to take control of the Presidency, Congress and the Supreme Court, thus threatening the rights of the citizens of the North.[61]

Free soil

"Free soil" was a Northern demand that the new lands opening up in the west be available to independent yeoman farmers and not be bought out by rich slave owners who would buy up the best land and work it with slaves, forcing the white farmers onto marginal lands. This was the basis of the Free Soil Party of 1848, and a main theme of the Republican Party.[62]

Tariffs

The Tariff of 1828, was a high protective tariff or tax on imports passed by Congress in 1828. It was labeled the "Tariff of Abominations"[63] by its southern detractors because of its effect on the Southern economy. The 1828 tariff was repealed after strong protests and threats of nullification by South Carolina.

The Democrats in Congress, controlled by Southerners, wrote the tariff laws in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, and kept reducing rates, so that the 1857 rates were the lowest since 1816. The South had no complaints but the low rates angered Northern industrialists and factory workers, especially in Pennsylvania, who demanded protection for their growing iron industry. The Whigs and Republicans favored high tariffs to stimulate industrial growth, and Republicans called for an increase in tariffs in the 1860 election. The increases were finally enacted in 1861 after Southerners resigned their seats in Congress.[64][65]

Historians in recent decades have minimized the tariff issue, noting that few people in 1860-61 said it was of central importance to them. Some secessionist documents do mention the tariff issue, though not nearly as often as the preservation of slavery. However, a few libertarian economists place more importance on the tariff issue.[66]

Election of Lincoln

The election of Lincoln in November 1860 was the final trigger for secession.[67] Efforts at compromise, including the "Corwin Amendment" and the "Crittenden Compromise", failed. Southern leaders feared that Lincoln would stop the expansion of slavery and put it on a course toward extinction. The slave states, which had already become a minority in the House of Representatives, were now facing a future as a perpetual minority in the Senate and Electoral College against an increasingly powerful North. Before Lincoln took office in March 1861, seven slave states had declared their secession and joined together to form the Confederacy.

Battle of Fort Sumter

The Lincoln Administration, just as the outgoing Buchanan administration before it, refused to turn over Ft. Sumter—located in the middle of the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet decided that it was impossible to be an independent nation with a foreign military fort in its leading harbor, so he ordered Confederate forces to attack. After a heavy bombardment on April 12–13, 1861, (with no casualties), the fort surrendered. Lincoln then called for 75,000 troops from the states to recapture the fort and other federal property. That meant marching a federal army through Virginia and North Carolina, so those states promptly joined the Confederacy (as did Tennessee and Arkansas). North and South the response to Ft. Sumter was an overwhelming, unstoppable demand for war to uphold national honor. Only Kentucky tried to remain neutral. Hundreds of thousands of young men across the land rushed to enlist, and the war was on.[68]

Secession begins

Secession of South Carolina

South Carolina did more to advance nullification and secession than any other Southern state. South Carolina adopted the "Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union" on December 24, 1860. It argued for states' rights for slave owners in the South, but contained a complaint about states' rights in the North in the form of opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act, claiming that Northern states were not fulfilling their federal obligations under the Constitution. All the alleged violations of the rights of Southern states were related to slavery.

Secession winter

The Confederacy: brown

*territories in light shades; control of Confederate territories disputed

Before Lincoln took office, seven states had declared their secession from the Union. They established a Southern government, the Confederate States of America on February 4, 1861.[69] They took control of federal forts and other properties within their boundaries with little resistance from outgoing President James Buchanan, whose term ended on March 4, 1861. Buchanan said that the Dred Scott decision was proof that the South had no reason for secession, and that the Union "was intended to be perpetual", but that "the power by force of arms to compel a State to remain in the Union" was not among the "enumerated powers granted to Congress".[70] One quarter of the U.S. Army—the entire garrison in Texas—was surrendered in February 1861 to state forces by its commanding general, David E. Twiggs, who then joined the Confederacy.

As Southerners resigned their seats in the Senate and the House, secession later enabled Republicans to pass bills for projects that had been blocked by Southern Senators before the war, including the Morrill Tariff, land grant colleges (the Morill Act), a Homestead Act, a trans-continental railroad (the Pacific Railway Acts), the National Banking Act and the authorization of United States Notes by the Legal Tender Act of 1862. The Revenue Act of 1861 introduced the income tax to help finance the war.

The Confederacy

Seven Deep South cotton states seceded by February 1861, starting with South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. These seven states formed the Confederate States of America (February 4, 1861), with Jefferson Davis as president, and a governmental structure closely modeled on the U.S. Constitution. Following the attack on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln called for a volunteer army from each state.

Within two months, four more Southern slave states declared their secession and joined the Confederacy: Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee. The northwestern portion of Virginia subsequently seceded from Virginia, joining the Union as the new state of West Virginia on June 20, 1863. By the end of 1861, Missouri and Kentucky were effectively under Union control, with Confederate state governments in exile.

The Union states

Twenty-three states remained loyal to the Union: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin. During the war, Nevada and West Virginia joined as new states of the Union. Tennessee and Louisiana were returned to Union military control early in the war.

The territories of Colorado, Dakota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington fought on the Union side. Several slave-holding Native American tribes supported the Confederacy, giving the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) a small, bloody civil war.[71][72][73]

Border states

The border states in the Union were West Virginia (which was separated from Virginia and became a new state), and four of the five northernmost slave states (Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky).

Maryland had numerous pro-Confederate officials who tolerated anti-Union rioting in Baltimore and the burning of bridges. Lincoln responded with martial law and sent in militia units from the North.[74] Before the Confederate government realized what was happening, Lincoln had seized firm control of Maryland and the District of Columbia, by arresting all the prominent secessionists and holding them without trial (they were later released).

In Missouri, an elected convention on secession voted decisively to remain within the Union. When pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne F. Jackson called out the state militia, it was attacked by federal forces under General Nathaniel Lyon, who chased the governor and the rest of the State Guard to the southwestern corner of the state. (See also: Missouri secession). In the resulting vacuum, the convention on secession reconvened and took power as the Unionist provisional government of Missouri.[75]

Kentucky did not secede; for a time, it declared itself neutral. When Confederate forces entered the state in September 1861, neutrality ended and the state reaffirmed its Union status, while trying to maintain slavery. During a brief invasion by Confederate forces, Confederate sympathizers organized a secession convention, inaugurated a governor, and gained recognition from the Confederacy. The rebel government soon went into exile and never controlled Kentucky.[76]

After Virginia's secession, a Unionist government in Wheeling asked 48 counties to vote on an ordinance to create a new state on October 24, 1861. A voter turnout of 34% approved the statehood bill (96% approving).[77] The inclusion of 24 secessionist counties[78] in the state and the ensuing guerrilla war[79] engaged about 40,000 Federal troops for much of the war.[80] Congress admitted West Virginia to the Union on June 20, 1863. West Virginia provided about 22-25,000 Union soldiers,[81] and at least 16,000 Confederate soldiers.[82]

A Unionist secession attempt occurred in East Tennessee, but was suppressed by the Confederacy, which arrested over 3000 men suspected of being loyal to the Union. They were held without trial.[83]

Overview

Over 10,000 military engagements took place during the war, 40% of them in Virginia and Tennessee.[84] Since separate articles deal with every major battle and many minor ones, this article only gives the broadest outline. For more information see List of American Civil War battles and Military leadership in the American Civil War.

The Beginning of the War, 1861

Lincoln's victory in the presidential election of 1860 triggered South Carolina's declaration of secession from the Union. By February 1861, six more Southern states made similar declarations. On February 7, the seven states adopted a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America and established their temporary capital at Montgomery, Alabama. A pre-war February Peace Conference of 1861 met in Washington in a failed attempt at resolving the crisis. The remaining eight slave states rejected pleas to join the Confederacy. Confederate forces seized most of the federal forts within their boundaries. President Buchanan protested but made no military response apart from a failed attempt to resupply Fort Sumter using the ship Star of the West, which was fired upon by South Carolina forces and turned back before it reached the fort.[85] However, governors in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania quietly began buying weapons and training militia units.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as President. In his inaugural address, he argued that the Constitution was a more perfect union than the earlier Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, that it was a binding contract, and called any secession "legally void".[86] He stated he had no intent to invade Southern states, nor did he intend to end slavery where it existed, but that he would use force to maintain possession of federal property. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union.[87]

The South sent delegations to Washington and offered to pay for the federal properties and enter into a peace treaty with the United States. Lincoln rejected any negotiations with Confederate agents because the Confederacy was not a legitimate government, and that making any treaty with it would be tantamount to recognition of it as a sovereign government.[88] However, Secretary of State William Seward engaged in unauthorized and indirect negotiations that failed.[88]

Fort Monroe in Virginia, Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, and Fort Pickens, Fort Jefferson, and Fort Taylor, all in Florida, were the remaining Union-held forts in the Confederacy, and Lincoln was determined to hold them all. Under orders from Confederate President Jefferson Davis, troops controlled by the Confederate government under P. G. T. Beauregard bombarded Fort Sumter on April 12, forcing its capitulation. Northerners rallied behind Lincoln's call for all the states to send troops to recapture the forts and to preserve the Union. With the scale of the rebellion apparently small so far, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers for 90 days.[89] For months before that, several Northern governors had discreetly readied their state militias; they began to move forces the next day.[90] Liberty Arsenal in Liberty, Missouri was seized eight days after Fort Sumter.

Four states in the upper South (Tennessee, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Virginia), which had repeatedly rejected Confederate overtures, now refused to send forces against their neighbors, declared their secession, and joined the Confederacy. To reward Virginia, the Confederate capital was moved to Richmond.[91] The city was the symbol of the Confederacy. Richmond was in a highly vulnerable location at the end of a tortuous Confederate supply line. Although Richmond was heavily fortified, supplies for the city would be reduced by Sherman's capture of Atlanta and cut off almost entirely when Grant besieged Petersburg and its railroads that supplied the Southern capital.

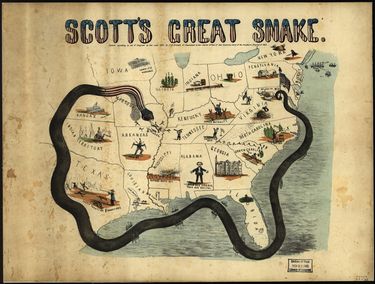

Anaconda Plan and blockade, 1861

Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the U.S. Army, devised the Anaconda Plan to win the war with as little bloodshed as possible.[92] His idea was that a Union blockade of the main ports would weaken the Confederate economy; then the capture of the Mississippi River would split the South. Lincoln adopted the plan in terms of a blockade to squeeze to death the Confederate economy, but overruled Scott's warnings that his new army was not ready for an offensive operation because public opinion demanded an immediate attack.[93]

In April 1861, Lincoln announced the Union blockade of all Southern ports; commercial ships could not get insurance and regular traffic ended. The South blundered in embargoing cotton exports in 1861 before the blockade was effective; by the time they realized the mistake it was too late. "King Cotton" was dead, as the South could export less than 10% of its cotton.[94] British investors built small, fast blockade runners that traded arms and luxuries brought in from Bermuda, Cuba and the Bahamas in return for high-priced cotton and tobacco.[95] When the Union Navy seized a blockade runner the ship and cargo were sold and the proceeds given to the Navy sailors; the captured crewmen were mostly British and they were simply released. The Southern economy nearly collapsed during the war. Shortages of food and supplies were caused by the blockade, the failure of Southern railroads, the loss of control of the main rivers, foraging by Northern armies, and the impressment of crops by Confederate armies. The standard of living fell even as large-scale printing of paper money caused inflation and distrust of the currency. By 1864 the internal food distribution had broken down, leaving cities without enough food and causing bread riots across the Confederacy.[96]

On March 8, 1862, the Confederate Navy waged a fight against the Union Navy when the ironclad CSS Virginia attacked the blockade. Against wooden ships, she seemed unstoppable. The next day, however, she had to fight the new Union warship USS Monitor in the Battle of the Ironclads.[97] Their battle ended in a draw. The Confederacy lost the Virginia when the ship was scuttled to prevent capture, and the Union built many copies of Monitor. Lacking the technology to build effective warships, the Confederacy attempted to obtain warships from Britain. The Union victory at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher in January 1865 closed the last useful Southern port and virtually ended blockade running.

Eastern Theater 1861–1863

Because of the fierce resistance of a few initial Confederate forces at Manassas, Virginia, in July 1861, a march by Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell on the Confederate forces there was halted in the First Battle of Bull Run, or First Manassas,[98] McDowell's troops were forced back to Washington, D.C., by the Confederates under the command of Generals Joseph E. Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard. It was in this battle that Confederate General Thomas Jackson received the nickname of "Stonewall" because he stood like a stone wall against Union troops.[99]

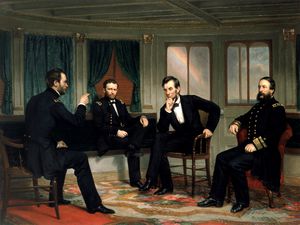

-

Generals Sherman, Grant and Sheridan, Postage Issue of 1937

Generals Sherman, Grant and Sheridan, Postage Issue of 1937

Alarmed at the loss, and in an attempt to prevent more slave states from leaving the Union, the U.S. Congress passed the Crittenden-Johnson Resolution on July 25 of that year, which stated that the war was being fought to preserve the Union and not to end slavery.

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan took command of the Union Army of the Potomac on July 26 (he was briefly general-in-chief of all the Union armies, but was subsequently relieved of that post in favor of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck), and the war began in earnest in 1862. Upon the strong urging of President Lincoln to begin offensive operations, McClellan attacked Virginia in the spring of 1862 by way of the peninsula between the York River and James River, southeast of Richmond. Although McClellan's army reached the gates of Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign,[100][101][102] Johnston halted his advance at the Battle of Seven Pines, then General Robert E. Lee and top subordinates James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson[103] defeated McClellan in the Seven Days Battles and forced his retreat. The Northern Virginia Campaign, which included the Second Battle of Bull Run, ended in yet another victory for the South.[104] McClellan resisted General-in-Chief Halleck's orders to send reinforcements to John Pope's Union Army of Virginia, which made it easier for Lee's Confederates to defeat twice the number of combined enemy troops.

Emboldened by Second Bull Run, the Confederacy made its first invasion of the North. General Lee led 45,000 men of the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5. Lincoln then restored Pope's troops to McClellan. McClellan and Lee fought at the Battle of Antietam[103] near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, the bloodiest single day in United States military history.[105] Lee's army, checked at last, returned to Virginia before McClellan could destroy it. Antietam is considered a Union victory because it halted Lee's invasion of the North and provided an opportunity for Lincoln to announce his Emancipation Proclamation.[106]

When the cautious McClellan failed to follow up on Antietam, he was replaced by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Burnside was soon defeated at the Battle of Fredericksburg[107] on December 13, 1862, when over twelve thousand Union soldiers were killed or wounded during repeated futile frontal assaults against Marye's Heights. After the battle, Burnside was replaced by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. Hooker, too, proved unable to defeat Lee's army; despite outnumbering the Confederates by more than two to one, he was humiliated in the Battle of Chancellorsville[108] in May 1863. He was replaced by Maj. Gen. George Meade during Lee's second invasion of the North, in June. Meade defeated Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg[109] (July 1 to July 3, 1863). This was the bloodiest battle of the war, and has been called the war's turning point. Pickett's Charge on July 3 is often considered the high-water mark of the Confederacy because it signaled the collapse of serious Confederate threats of victory. Lee's army suffered 28,000 casualties (versus Meade's 23,000).[110] However, Lincoln was angry that Meade failed to intercept Lee's retreat, and after Meade's inconclusive fall campaign, Lincoln turned to the Western Theater for new leadership. At the same time the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg surrendered, giving the Union control of the Mississippi River, permanently isolating the western Confederacy, and producing the new leader Lincoln needed, Ulysses S. Grant.

Western Theater 1861–1863

While the Confederate forces had numerous successes in the Eastern Theater, they were defeated many times in the West. They were driven from Missouri early in the war as a result of the Battle of Pea Ridge.[111] Leonidas Polk's invasion of Columbus, Kentucky ended Kentucky's policy of neutrality and turned that state against the Confederacy. Nashville and central Tennessee fell to the Union early in 1862, leading to attrition of local food supplies and livestock and a breakdown in social organization.

The Mississippi was opened to Union traffic to the southern border of Tennessee with the taking of Island No. 10 and New Madrid, Missouri, and then Memphis, Tennessee. In April 1862, the Union Navy captured New Orleans[112] without a major fight, which allowed Union forces to begin moving up the Mississippi. Only the fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, prevented Union control of the entire river.

General Braxton Bragg's second Confederate invasion of Kentucky ended with a meaningless victory over Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell at the Battle of Perryville,[113] although Bragg was forced to end his attempt at invading Kentucky and retreat due to lack of support for the Confederacy in that state. Bragg was narrowly defeated by Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans at the Battle of Stones River[114] in Tennessee.

The one clear Confederate victory in the West was the Battle of Chickamauga. Bragg, reinforced by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's corps (from Lee's army in the east), defeated Rosecrans, despite the heroic defensive stand of Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas. Rosecrans retreated to Chattanooga, which Bragg then besieged.

The Union's key strategist and tactician in the West was Ulysses S. Grant, who won victories at Forts Henry and Donelson (by which the Union seized control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers); the Battle of Shiloh;[115] and the Battle of Vicksburg,[116] which cemented Union control of the Mississippi River and is considered one of the turning points of the war. Grant marched to the relief of Rosecrans and defeated Bragg at the Third Battle of Chattanooga,[117] driving Confederate forces out of Tennessee and opening a route to Atlanta and the heart of the Confederacy.

Trans-Mississippi Theater 1861–1865

Guerrilla activity turned much of Missouri into a battleground. Missouri had, in total, the third-most battles of any state during the war.[118] The other states of the west, though geographically isolated from the battles to the east, saw numerous small-scale military actions. Battles in the region served to secure Missouri, Indian Territory, and New Mexico Territory for the Union. Confederate incursions into New Mexico territory were repulsed in 1862 and a Union campaign to secure Indian Territory succeeded in 1863. Late in the war, the Union's Red River Campaign was a failure. Texas remained in Confederate hands throughout the war, but was cut off from the rest of the Confederacy after the capture of Vicksburg in 1863 gave the Union control of the Mississippi River.

Conquest of Virginia and End of War: 1864–1865

At the beginning of 1864, Lincoln made Grant commander of all Union armies. Grant made his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, and put Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in command of most of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of total war and believed, along with Lincoln and Sherman, that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would bring an end to the war.[119] This was total war not in terms of killing civilians but rather in terms of destroying homes, farms, and railroads. Grant devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the entire Confederacy from multiple directions. Generals George Meade and Benjamin Butler were ordered to move against Lee near Richmond, General Franz Sigel (and later Philip Sheridan) were to attack the Shenandoah Valley, General Sherman was to capture Atlanta and march to the sea (the Atlantic Ocean), Generals George Crook and William W. Averell were to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks was to capture Mobile, Alabama.

Union forces in the East attempted to maneuver past Lee and fought several battles during that phase ("Grant's Overland Campaign") of the Eastern campaign. Grant's battles of attrition at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor[120] resulted in heavy Union losses, but forced Lee's Confederates to fall back repeatedly. An attempt to outflank Lee from the south failed under Butler, who was trapped inside the Bermuda Hundred river bend. Grant was tenacious and, despite astonishing losses (over 65,000 casualties in seven weeks),[121] kept pressing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia back to Richmond. He pinned down the Confederate army in the Siege of Petersburg, where the two armies engaged in trench warfare for over nine months.

Grant finally found a commander, General Philip Sheridan, aggressive enough to prevail in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Sheridan defeated Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early in a series of battles, including a final decisive defeat at the Battle of Cedar Creek. Sheridan then proceeded to destroy the agricultural base of the Shenandoah Valley,[122] a strategy similar to the tactics Sherman later employed in Georgia.

Meanwhile, Sherman marched from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood along the way. The fall of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, was a significant factor in the reelection of Lincoln as president.[123] Hood left the Atlanta area to menace Sherman's supply lines and invade Tennessee in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign.[124] Union Maj. Gen. John Schofield defeated Hood at the Battle of Franklin, and George H. Thomas dealt Hood a massive defeat at the Battle of Nashville, effectively destroying Hood's army.

Leaving Atlanta, and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched with an unknown destination, laying waste to about 20% of the farms in Georgia in his "March to the Sea". He reached the Atlantic Ocean at Savannah, Georgia in December 1864. Sherman's army was followed by thousands of freed slaves; there were no major battles along the March. Sherman turned north through South Carolina and North Carolina to approach the Confederate Virginia lines from the south,[125] increasing the pressure on Lee's army.

Lee's army, thinned by desertion and casualties, was now much smaller than Grant's. Union forces won a decisive victory at the Battle of Five Forks on April 1, forcing Lee to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. The Confederate capital fell[126] to the Union XXV Corps, composed of black troops. The remaining Confederate units fled west and after a defeat at Sayler's Creek, it became clear to Robert E. Lee that continued fighting against the United States was both tactically and logistically impossible.

Confederacy Surrenders

Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, at the McLean House in the village of Appomattox Court House.[127] In an untraditional gesture and as a sign of Grant's respect and anticipation of peacefully folding the Confederacy back into the Union, Lee was permitted to keep his officer's saber and his horse, Traveller. On April 14, 1865, President Lincoln was shot. Lincoln died early the next morning, and Andrew Johnson became President.

Events leading to Lee's surrender began with the capture of key Confederate officers Richard S. Ewell and Richard H. Anderson on April 6, following Confederate defeat at the battle of Sayler's Creek. On April 8, Union cavalry under Major General George Armstrong Custer destroyed three trains of Confederate supplies at Appomattox Station, leading to the surrender of General Lee the next day.[128] General St. John Richardson Liddell's army surrendered after the loss of the Confederate fortifications at the Battle of Spanish Fort in Alabama, also on April 9.

Unaware of the surrender of Lee, on April 16 the last major battles of the war were fought at the Battle of Columbus, Georgia and the Battle of West Point. Both towns surrendered to Wilson's Raiders.

On April 21, John S. Mosby’s raiders of the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry was disbanded, and on April 26, General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered his troops to Sherman at Bennett Place in Durham, North Carolina. Surrendering on May 4 and 5 were the Confederate departments of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana regiments and the District of the Gulf. The Confederate President was captured on May 10 and the surrender of the Department of Florida and South Georgia happened the same day. Confederate Brigadier General "Jeff" Meriwether Thompson surrendered his brigade the next day and the day following saw the surrender of the Confederate forces of North Georgia.

On June 23, 1865, at Fort Towson in the Choctaw Nations' area of the Oklahoma Territory, Stand Watie signed a cease-fire agreement with Union representatives, becoming the last Confederate general in the field to stand down. The last Confederate ship to surrender was the CSS Shenandoah, whose officers did not know of the end of the war until August 2. Not wanting to surrender to Federal authorities, the ship's commander plotted a course for the country of his ship's birth, so that they surrendered on November 6, 1865, in Liverpool, England.[129] These surrenders marked the conclusion of the American Civil War.

Slavery during the war

At the beginning of the war, some Union commanders thought they were supposed to return escaped slaves to their masters. By 1862, when it became clear that this would be a long war, the question of what to do about slavery became more general. The Southern economy and military effort depended on slave labor. It began to seem unreasonable to protect slavery while blockading Southern commerce and destroying Southern production. As one Congressman put it, the slaves "...cannot be neutral. As laborers, if not as soldiers, they will be allies of the rebels, or of the Union."[130] The same Congressman—and his fellow Radical Republicans—put pressure on Lincoln to rapidly emancipate the slaves, whereas moderate Republicans came to accept gradual, compensated emancipation and colonization.[131] Copperheads, the border states and War Democrats opposed emancipation, although the border states and War Democrats eventually accepted it as part of total war needed to save the Union.

In 1861, Lincoln expressed the fear that premature attempts at emancipation would mean the loss of the border states, and that "to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game."[132] At first, Lincoln reversed attempts at emancipation by Secretary of War Simon Cameron and Generals John C. Frémont (in Missouri) and David Hunter (in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida) to keep the loyalty of the border states and the War Democrats.

Lincoln warned the border states that a more radical type of emancipation would happen if his gradual plan based on compensated emancipation and voluntary colonization was rejected.[133] Only the District of Columbia accepted Lincoln's gradual plan, and Lincoln mentioned his Emancipation Proclamation to members of his cabinet on July 21, 1862. Secretary of State William H. Seward told Lincoln to wait for a victory before issuing the proclamation, as to do otherwise would seem like "our last shriek on the retreat".[134] In September 1862 the Battle of Antietam provided this opportunity, and the subsequent War Governors' Conference added support for the proclamation.[135] Lincoln had already published a letter[136] encouraging the border states especially to accept emancipation as necessary to save the Union. Lincoln later said that slavery was "somehow the cause of the war".[137] Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, and his final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. In his letter to Hodges, Lincoln explained his belief that "If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong ... And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling ... I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me."[138]

Since the Emancipation Proclamation was based on the President's war powers, it only included territory held by Confederates at the time. However, the Proclamation became a symbol of the Union's growing commitment to add emancipation to the Union's definition of liberty.[139] Lincoln also played a leading role in getting Congress to vote for the Thirteenth Amendment,[140] which made emancipation universal and permanent.

Enslaved African Americans did not wait for Lincoln's action before escaping and seeking freedom behind Union lines. From early years of the war, hundreds of thousands of African Americans escaped to Union lines, especially in occupied areas like Nashville, Norfolk and the Hampton Roads region in 1862, Tennessee from 1862 on, the line of Sherman's march, etc. So many African Americans fled to Union lines that commanders created camps and schools for them, where both adults and children learned to read and write. The American Missionary Association entered the war effort by sending teachers south to such contraband camps, for instance establishing schools in Norfolk and on nearby plantations. In addition, nearly 200,000 African-American men served as soldiers and sailors with Union troops. Most of those were escaped slaves.

Confederates enslaved captured black Union soldiers, and black soldiers especially were shot when trying to surrender at the Fort Pillow Massacre.[141] This led to a breakdown of the prisoner exchange program[142] and the growth of prison camps such as Andersonville prison in Georgia,[143] where almost 13,000 Union prisoners of war died of starvation and disease.[144]

In spite of the South's shortage of soldiers, most Southern leaders — until 1865 — opposed enlisting slaves. They used them as laborers to support the war effort. As Howell Cobb said, "If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong." Confederate generals Patrick Cleburne and Robert E. Lee argued in favor of arming blacks late in the war, and Jefferson Davis was eventually persuaded to support plans for arming slaves to avoid military defeat. The Confederacy surrendered at Appomattox before this plan could be implemented.[145]

Historian John D. Winters, in The Civil War in Louisiana (1963), referred to the exhilaration of the slaves when the Union Army came through Louisiana: "As the troops moved up to Alexandria, the Negroes crowded the roadsides to watch the passing army. They were 'all frantic with joy, some weeping, some blessing, and some dancing in the exuberance of their emotions.' All of the Negroes were attracted by the pageantry and excitement of the army. Others cheered because they anticipated the freedom to plunder and to do as they pleased now that the Federal troops were there."[146]

The Emancipation Proclamation[147] greatly reduced the Confederacy's hope of getting aid from Britain or France. Lincoln's moderate approach succeeded in getting border states, War Democrats and emancipated slaves fighting on the same side for the Union. The Union-controlled border states (Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia) were not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation. All abolished slavery on their own, except Kentucky and Delaware.[148] The great majority of the 4 million slaves were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, as Union armies moved South. The 13th amendment,[149] ratified December 6, 1865, finally made slavery illegal everywhere in the United States, thus freeing the remaining slaves—65,000 in Kentucky (as of 1865),[150] 1,800 in Delaware, and 18 in New Jersey as of 1860.[151]

Historian Stephen Oates said that many myths surround Lincoln: "man of the people", "true Christian", "arch villain" and racist. The belief that Lincoln was racist was caused by an incomplete picture of Lincoln, such as focusing on only selective quoting of statements Lincoln made to gain the support of the border states and Northern Democrats, and ignoring the many things he said against slavery, and the military and political context within which such statements were made. Oates said that Lincoln's letter to Horace Greeley has been "persistently misunderstood and misrepresented" for such reasons.[152]

Blocking international intervention

The Confederacy's best hope was military intervention into the war by Britain and France against the Union.[153] The Union, under Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward worked to block this, and threatened war if any country officially recognized the existence of the Confederate States of America (none ever did). In 1861, Southerners voluntarily embargoed cotton shipments, hoping to start an economic depression in Europe that would force Britain to enter the war in order to get cotton. Cotton diplomacy proved a failure as Europe had a surplus of cotton, while the 1860–62 crop failures in Europe made the North's grain exports of critical importance. It was said that "King Corn was more powerful than King Cotton", as US grain went from a quarter of the British import trade to almost half.[154]

When Britain did face a cotton shortage, it was temporary, being replaced by increased cultivation in Egypt and India. Meanwhile, the war created employment for arms makers, iron workers, and British ships to transport weapons.[155]

Charles Francis Adams proved particularly adept as minister to Britain for the U.S. and Britain was reluctant to boldly challenge the blockade. The Confederacy purchased several warships from commercial ship builders in Britain. The most famous, the CSS Alabama, did considerable damage and led to serious postwar disputes. However, public opinion against slavery created a political liability for European politicians, especially in Britain (who had herself abolished slavery in her own colonies in 1834). War loomed in late 1861 between the U.S. and Britain over the Trent Affair, involving the U.S. Navy's boarding of a British mail steamer to seize two Confederate diplomats. However, London and Washington were able to smooth over the problem after Lincoln released the two.

In 1862, the British considered mediation—though even such an offer would have risked war with the U.S. Lord Palmerston reportedly read Uncle Tom’s Cabin three times when deciding on this.[156] The Union victory in the Battle of Antietam caused them to delay this decision. The Emancipation Proclamation further reinforced the political liability of supporting the Confederacy. Despite sympathy for the Confederacy, France's own seizure of Mexico ultimately deterred them from war with the Union. Confederate offers late in the war to end slavery in return for diplomatic recognition were not seriously considered by London or Paris.

Victory and aftermath

| Union | CSA | |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 22,100,000 (71%) | 9,100,000 (29%) |

| Free population | 21,700,000 | 5,600,000 |

| Slave population, 1860 | 400,000 | 3,500,000 |

| Soldiers | 2,100,000 (67%) | 1,064,000 (33%) |

| Railroad miles | 21,788 (71%) | 8,838 (29%) |

| Manufactured items | 90% | 10% |

| Firearm production | 97% | 3% |

| Bales of cotton in 1860 | Negligible | 4,500,000 |

| Bales of cotton in 1864 | Negligible | 300,000 |

| Pre-war U.S. exports | 30% | 70% |

Historians have debated whether the Confederacy could have won the war. Most scholars emphasize that the Union held an insurmountable long-term advantage over the Confederacy in terms of industrial strength and population. Confederate actions, they argue, only delayed defeat. Southern historian Shelby Foote expressed this view succinctly: "I think that the North fought that war with one hand behind its back...If there had been more Southern victories, and a lot more, the North simply would have brought that other hand out from behind its back. I don't think the South ever had a chance to win that War."[158] The Confederacy sought to win independence by out-lasting Lincoln; however, after Atlanta fell and Lincoln defeated McClellan in the election of 1864, all hope for a political victory for the South ended. At that point, Lincoln had succeeded in getting the support of the border states, War Democrats, emancipated slaves, Britain, and France. By defeating the Democrats and McClellan, he also defeated the Copperheads and their peace platform.[159] Lincoln had found military leaders like Grant and Sherman who would press the Union's numerical advantage in battle over the Confederate Armies. Generals who did not shy from bloodshed won the war, and from the end of 1864 onward there was no hope for the South.

On the other hand, James McPherson has argued that the North’s advantage in population and resources made Northern victory likely, but not inevitable. Confederates did not need to invade and hold enemy territory to win, but only needed to fight a defensive war to convince the North that the cost of winning was too high. The North needed to conquer and hold vast stretches of enemy territory and defeat Confederate armies to win.[160]

Also important were Lincoln's eloquence in rationalizing the national purpose and his skill in keeping the border states committed to the Union cause. Although Lincoln's approach to emancipation was slow, the Emancipation Proclamation was an effective use of the President's war powers.[161]

The Confederate government failed in its attempt to get Europe involved in the war militarily, particularly the United Kingdom and France. Southern leaders needed to get European powers to help break up the blockade the Union had created around the Southern ports and cities. Lincoln's naval blockade was 95% effective at stopping trade goods; as a result, imports and exports to the South declined significantly. The abundance of European cotton and the United Kingdom's hostility to the institution of slavery, along with Lincoln's Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico naval blockades, severely decreased any chance that either the United Kingdom or France would enter the war.

The more industrialized economy of the North aided in the production of arms, munitions and supplies, as well as finances and transportation. The table shows the relative advantage of the Union over the Confederate States of America (CSA) at the start of the war. The advantages widened rapidly during the war, as the Northern economy grew, and Confederate territory shrank and its economy weakened. The Union population was 22 million and the South 9 million in 1861. The Southern population included more than 3.5 million slaves and about 5.5 million whites, thus leaving the South's white population outnumbered by a ratio of more than four to one.[162] The disparity grew as the Union controlled an increasing amount of southern territory with garrisons, and cut off the trans-Mississippi part of the Confederacy. The Union at the start controlled over 80% of the shipyards, steamships, riverboats, and the Navy. It augmented these by a massive shipbuilding program. This enabled the Union to control the river systems and to blockade the entire southern coastline.[163] Excellent railroad links between Union cities allowed for the quick and cheap movement of troops and supplies. Transportation was much slower and more difficult in the South which was unable to augment its much smaller rail system, repair damage, or even perform routine maintenance.[164] The failure of Davis to maintain positive and productive relationships with state governors (especially governor Joseph E. Brown of Georgia and governor Zebulon Baird Vance of North Carolina) damaged his ability to draw on regional resources.[165] The Confederacy's "King Cotton" misperception of the world economy led to bad diplomacy, such as the refusal to ship cotton before the blockade started.[166] The Emancipation Proclamation enabled African-Americans, both free blacks and escaped slaves, to join the Union Army. About 190,000 volunteered,[167] further enhancing the numerical advantage the Union armies enjoyed over the Confederates, who did not dare emulate the equivalent manpower source for fear of fundamentally undermining the legitimacy of slavery. Emancipated slaves mostly handled garrison duties, and fought numerous battles in 1864–65.[168] European immigrants joined the Union Army in large numbers, including 177,000 born in Germany and 144,000 born in Ireland.[169]

Reconstruction

Northern leaders agreed that victory would require more than the end of fighting. It had to encompass the two war goals: secession had to be repudiated and all forms of slavery had to be eliminated. They disagreed sharply on the criteria for these goals. They also disagreed on the degree of federal control that should be imposed on the South, and the process by which Southern states should be reintegrated into the Union.

Reconstruction, which began early in the war and ended in 1877, involved a complex and rapidly changing series of federal and state policies. The long-term result came in the three Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution: the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. Reconstruction ended in the different states at different times, the last three by the Compromise of 1877.

Results

Slavery effectively ended in the U.S. in the spring of 1865 when the Confederate armies surrendered. All slaves in the Confederacy were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, which stipulated that slaves in Confederate-held areas were free. Slaves in the border states and Union-controlled parts of the South were freed by state action or (on December 6, 1865) by the Thirteenth Amendment. The full restoration of the Union was the work of a highly contentious postwar era known as Reconstruction. The war produced about 1,030,000 casualties (3% of the population), including about 620,000 soldier deaths—two-thirds by disease.[170] The war accounted for roughly as many American deaths as all American deaths in other U.S. wars combined.[171] The causes of the war, the reasons for its outcome, and even the name of the war itself are subjects of lingering contention today. About 4 million black slaves were freed in 1861–65. Based on 1860 census figures, 8% of all white males aged 13 to 43 died in the war, including 6% in the North and 18% in the South.[172][173] About 56,000 soldiers died in prisons during the Civil War.[174] One reason for the high number of battle deaths during the war was the use of Napoleonic tactics such as charges. With the advent of more accurate rifled barrels, Minié balls and (near the end of the war for the Union army) repeating firearms such as the Spencer repeating rifle and a few experimental Gatling guns, soldiers were devastated when standing in lines in the open. This gave birth to trench warfare, a tactic heavily used during World War I.

Filmography

- Civil War Minutes: Union (2001)

- Civil War Minutes: Confederate (2007)

- The Civil War (TV series) (1990)

- Gone with the Wind (film) (1939)

- Glory (film) (1989)

- Gods and Generals (film) (2003)

- Cold Mountain (film) (2003)

- The Red Badge of Courage (film) (1951)

- Sommersby (1993)

- Andersonville (film) (1996)

- The Birth of a Nation (1915)

- Gettysburg (film) (1993)

- Shenandoah (film) (1965)

- The Colt (film) (2005)

- The Blue and the Gray (1982)

- The Hunley (1999)

Notes

- ↑ Frank J. Williams, "Doing Less and Doing More: The President and the Proclamation—Legally, Militarily and Politically," in Harold Holzer, ed. The Emancipation Proclamation (2006) pp. 74–5.

- ↑ Howard Jones, Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War (1999) p. 154.

- ↑ "Killing ground: photographs of the Civil War and the changing American landscape". John Huddleston (2002). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801867738

- ↑ Hart, Albert Bushnell (1906). Slavery and abolition, 1831-1841. The American Nation: A History from Original Sources by Associated Scholars, Albert Bushnell Hart. 16. Harper & brothers. pp. 152–155. ISBN 0790557002.

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln, House Divided Speech, Springfield, Illinois, June 16, 1858.

- ↑ Glenn M. Linden (2001). Voices from the Gathering Storm: The Coming of the American Civil War. United States: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 236. ISBN 0842029990. http://books.google.com/?id=F20ZsA5ZeeEC&pg=PA184&lpg=PA184&dq=Prevent+%22any+of+our+friends+from+demoralizing+themselves%22. "Prevent, as far as possible, any of our friends from demoralizing themselves, and our cause, by entertaining propositions for compromise of any sort, on slavery extension. There is no possible compromise upon it, but which puts us under again, and leaves all our work to do over again. Whether it be a Mo. Line, or Eli Thayer's Pop. Sov. It is all the same. Let either be done, & immediately filibustering and extending slavery recommences. On that point hold firm, as with a chain of steel. – Abraham Lincoln to Elihu B. Washburne, December 13, 1860"

- ↑ Let there be no compromise on the question of extending slavery. If there be, all our labor is lost, and, ere long, must be done again. The dangerous ground—that into which some of our friends have a hankering to run—is Pop. Sov. Have none of it. Stand firm. The tug has to come, & better now, than any time hereafter. – Abraham Lincoln to Lyman Trumbull, December 10, 1860.

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, pp. 241, 253.

- ↑ Declarations of Causes for: Georgia, Adopted in January 29, 1861; Mississippi, Adopted in 1861 (no exact date found); South Carolina, Adopted in December 24, 1860; Texas, Adopted in February 2, 1861.

- ↑ The New Heresy, Southern Punch, editor John Wilford Overall, September 19, 1864 is one of many references that indicate that the Republican hope of gradually ending slavery was the Southern fear. It said in part, "Our doctrine is this: WE ARE FIGHTING FOR INDEPENDENCE THAT OUR GREAT AND NECESSARY DOMESTIC INSTITUTION OF SLAVERY SHALL BE PRESERVED."

- ↑ Lincoln's Speech in Chicago, December 10, 1856 in which he said, "We shall again be able not to declare, that 'all States as States, are equal,' nor yet that 'all citizens as citizens are equal,' but to renew the broader, better declaration, including both these and much more, that 'all men are created equal.'"; Also, Lincoln's Letter to Henry L. Pierce, April 6, 1859.

- ↑ The People's Chronology, 1994 by James Trager.

- ↑ William E. Gienapp, "The Crisis of American Democracy: The Political System and the Coming of the Civil War." in Boritt ed. Why the Civil War Came 79–123.

- ↑ McPherson, Battle Cry pp. 88–91.

- ↑ Most of her slave owners are "decent, honorable people, themselves victims" of that institution. Much of her description was based on personal observation, and the descriptions of Southerners; she herself calls them and Legree representatives of different types of masters.;Gerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, p. 68; Stowe, Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1953) p. 39.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 201–204, 299–327.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, p. 208.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Fox Butterfield; All God's Children p. 17.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 212–213.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 356–384.

- ↑ James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom 1988 p 242, 255, 282–83. Maps on p. 101 (The Southern Economy) and p. 236 (The Progress of Secession) are also relevant.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 503–505.

- ↑ James G. Randall and David Donald, Civil War and Reconstruction (1961) p. 68

- ↑ Randall and Donald, p. 67

- ↑ James McPherson, Drawn with the Sword, p. 15.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, p. 275.

- ↑ Roger B. Taney: Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857).

- ↑ First Lincoln Douglas Debate at Ottawa, Illinois August 21, 1858.

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln, Speech at New Haven, Conn., March 6, 1860.

- ↑ McPherson, Battle Cry, p. 195.

- ↑ John Townsend, The Doom of Slavery in the Union, its Safety out of it, October 29, 1860.

- ↑ McPherson, Battle Cry, p. 243.

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, p. 461.

- ↑ William C. Davis, Look Away, pp. 130–140.

- ↑ William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion, p. 42.

- ↑ A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union, February 2, 1861 – A declaration of the causes which impel the State of Texas to secede from the Federal Union.

- ↑ Winkler, E. "A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union.". Journal of the Secession Convention of Texas. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_texsec.asp. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- ↑ Speech of E. S. Dargan to the Secession Convention of Alabama, January 11, 1861, in Wikisource.

- ↑ Schlesinger Age of Jackson, p. 190.

- ↑ David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage (2006) p 197, 409; Stanley Harrold, The Abolitionists and the South, 1831–1861 (1995) p. 62; Jane H. and William H. Pease, "Confrontation and Abolition in the 1850s" Journal of American History (1972) 58(4): 923–937.

- ↑ Eric Foner. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (1970), p. 9.

- ↑ William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion: Secessionists Triumphant 1854–1861, pp. 9–24.

- ↑ William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion, Secessionists Triumphant, pp. 269–462, p. 274 (The quote about slave states "encircled by fire" is from the New Orleans Delta, May 13, 1860).

- ↑ Charles S. Sydnor, The Development of Southern Sectionalism 1819-1848 (1948)

- ↑ Robert Royal Russel, Economic Aspects of Southern Sectionalism, 1840-1861 (1973)

- ↑ Adam Rothman, Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South (2005).

- ↑ Kenneth M. Stampp, The Imperiled Union: Essays on the Background of the Civil War (1981) p 198; Woodworth, ed. The American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research (1996), 145 151 505 512 554 557 684; Richard Hofstadter, The Progressive Historians: Turner, Beard, Parrington (1969).

- ↑ Clement Eaton, Freedom of Thought in the Old South (1940)

- ↑ John Hope Franklin, The Militant South 1800-1861 (1956).

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln, Cooper Union Address, New York, February 27, 1860.

- ↑ Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (1972) pp 648-69.

- ↑ James McPherson, "Antebellum Southern Exceptionalism: A New Look at an Old Question," Civil War History 29 (September 1983).

- ↑ David M. Potter, "The Historian's Use of Nationalism and Vice Versa," American Historical Review, Vol. 67, No. 4 (July 1962), pp. 924-950 in JSTOR.

- ↑ C. Vann Woodward, American Counterpoint: Slavery and Racism in the North-South Dialogue (1971), p.281.

- ↑ Bertram Wyatt-Brown, The Shaping of Southern Culture: Honor, Grace, and War, 1760s-1880s (2000).

- ↑ Avery Craven, The Growth of Southern Nationalism, 1848-1861 (1953).

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Forrest McDonald, States' Rights and the Union: Imperium in Imperio, 1776-1876 (2002)

- ↑ James McPherson, This Mighty Scourge, pp. 3–9.

- ↑ Before 1850, slave owners controlled the presidency for fifty years, the Speaker's chair for forty-one years, and the chairmanship of the House Ways and Means Committee that set tariffs for forty-two years, while 18 of 31 Supreme Court justices owned slaves. Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860 (2000) pp. 1-9

- ↑ Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (1970)

- ↑ [1], Office of the Clerk [2]

- ↑ Frank Taussig, The Tariff History of the United States (1931), pp 115-61

- ↑ Richard Hofstadter, "The Tariff Issue on the Eve of the Civil War," The American Historical Review Vol. 44, No. 1 (Oct., 1938), pp. 50-55 full text in JSTOR

- ↑ Mark Thornton and Robert B. Ekelund, Jr., Tariffs, Blockades, and Inflation: The Economics of the Civil War (2004)

- ↑ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, p. 485.

- ↑ Maury Klein, Days of Defiance: Sumter, Secession, and the Coming of the Civil War (1999)

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 254.

- ↑ President James Buchanan, Message of December 8, 1860 online.

- ↑ Gibson, Arrell. Oklahoma, a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) pg. 117–120

- ↑ "United States Volunteers — Indian Troops". civilwararchive.com. 2008-01-28. http://www.civilwararchive.com/Unreghst/unindtr.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ "Civil War Refugees". Oklahoma Historical Society. Oklahoma State University. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/C/CI013.html. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ McPherson, Battle Cry, pp. 284–287.

- ↑ Nevins, The War for the Union (1959) 1:119-29

- ↑ Nevins, The War for the Union (1959) 1:129-36

- ↑ "A State of Convenience, The Creation of West Virginia". West Virginia Archives & History. http://www.wvculture.org/History/statehood/statehood10.html.

- ↑ Curry, Richard Orr, A House Divided, A Study of the Statehood Politics & the Copperhead Movement in West Virginia, Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1964, map on page 49

- ↑ Weigley, Russell F., "A Great Civil War, A Military and Political History 1861-1865, Indiana Univ. Press, 2000, pg. 55

- ↑ McPherson, James M., Battle Cry of Freedom, The Civil War Era, Oxford Univ. Press, 2003, pg. 303

- ↑ "West Virginia's Civil War Soldiers Database". George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War. http://www.shepherd.edu/gtmcweb/research_database.html.

- ↑ Jack L. Dickinson, "Tattered Uniforms and Bright Bayonets, West Virginia's Confederate Soldiers", 2nd revised ed., 2004, pg. 75. Enumerates 16,355 individual soldiers.

- ↑ Mark Neely, Confederate Bastille: Jefferson Davis and Civil Liberties 1993 pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Gabor Boritt, ed. War Comes Again (1995) p. 247.

- ↑ McPherson, Battle Cry, pp. 234–266.

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, Monday, March 4, 1861.

- ↑ Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 572–573.